Institutional quality and economic growth

Foreign investment and quality of human resources are the channels that link institutions to economic development.

Published by Matteo Roscio. .

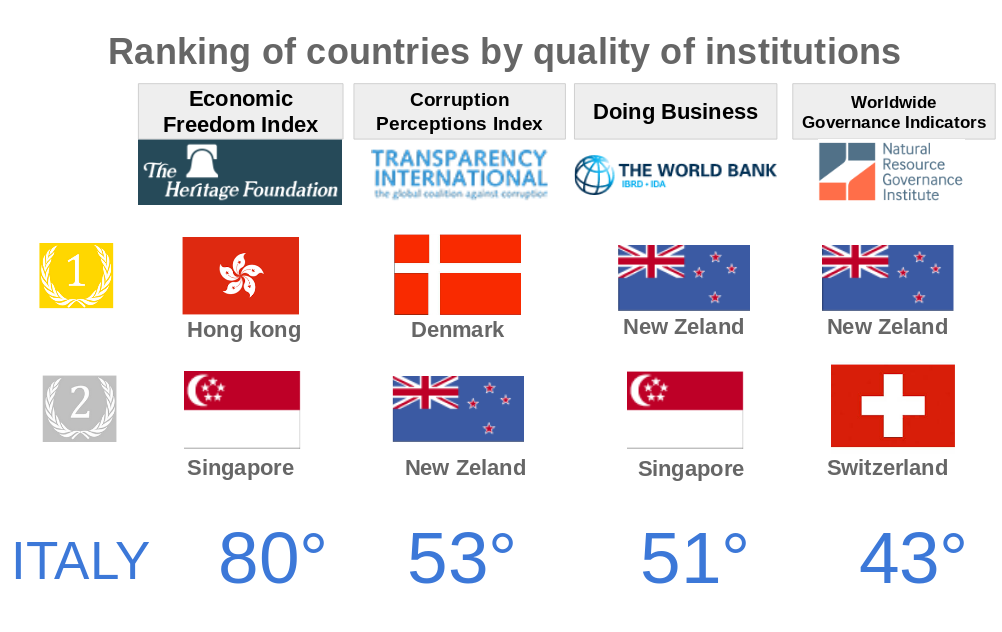

Macroeconomic analysis Economic policy Global economic trendsInstitutional quality has recently gained increasingly attention among the economic debates and by now it is widely recognized that efficient institutional structures are an essential factor to the economic development. Many international organizations have developed projects capable of evaluating the nations institutional quality worldwide; the most important among them are:

- Economic Freedom Index published by Heritage Fondation (the database is available at this link);

- Corruption Perceptions Index published by Transparency International (the database is available at this link);

- Doing Business published by World Bank (the database is available at this link);

- Worldwide Governance Indicators published by Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and Brookings Institution (the database is available at this link).

The variety of sources and the similarity in results allow us to obtain a good evaluation of institutional quality for each country. For instance, the quality of Italian institutions ranks between the 40th and the 80th position by these indexes, providing one way to explain the subdued economic growth of Italy during last years.

This article does not focus on the Italian case,

but rather on the channels that the economic literature identifies as the most important ones through which institutional quality influences economic growth in each country.

Institutional quality boosts economic growth because of its ability to attract capital

It is clear that a high-quality institutional framework is essential to economic growth, nevertheless economic literature explains little about why and how this happens. In this sense three economists Laura Alfaro, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan and Vadym Volosovych offered their contribution in 2005 by publishing an empirical study (Why Doesn't Capital Flow from Rich to Poor Countries? An Empirical Investigation). The purpose of that research was to analyze the reasons behind the fact that capital does not flow from the developed countries to the developing ones, in contrast with the economic theory of the decreasing marginal productivity of capital. The research pointed out how the key factor in determining the direction of the international investments was institutional quality while other elements such as asymmetric information, geographical distance and taxation levels didn’t account significantly.

The capability to attract capital is therefore one of the channel through which institutional quality boosts economic development. Countries where property rights are guaranteed, bureaucracy is easy, jurisdiction is fast and the government is able to enforce contracts, rules and free competition, are incredibly attractive from an investor's point of view. On the opposite, investors rarely bring their capitals where government authority is weak or based on extractive institution which means inclined to expropriation and little respect of property rights.

The second channel through which institutional quality improve economic growth is the ability to train high-skilled human capital

By the term “human capital” we generally mean the sum of skills, knowledge and competences owned by a worker, such capabilities are both developed during education and work-research period. The human capital level of a country is believed to be high if its company and its research centres employ highly qualified personnel. The concept of human capital is intrinsically linked to economic growth. Along with technological innovation, this is the most important factor in influencing the level of productivity, that is the ability to adding value to the factors of production. Moreover, productivity depends on human capital itself.

Obviously, countries that are able to train or attract highly qualified personnel show higher level of productivity

ensuring growth and innovation. On the contrary countries which suffer from 'brain drain' or which are not able to ensure

an adequate education to its future workers, risk to develop a stagnant economy and an underdeveloped productivity.

Theoretically many reasons exist to assume that institutional quality plays a main role in training human capital;

first of all the lack or low diffusion of corruptive practices promotes a social structure based on meritocracy that allow

individuals to undertake courses of studies which are literally

investment in human capital; on the other hand, where corruption is widespread,

social mobility mechanism are blocked and such investment does not produce an adequate return.

Moreover, the stability of a country and the ability of its government to enforce effective democratic power are another essential requisite to shape

high-quality human capital: where governments guarantee security against tensions and conflicts, citizens have the opportunity to undertake their personal

training path, while the presence of situations of war or political instability prevents that chance.

Finally, democratic states, differently to dictatorships, do not have to sustain military-crony frameworks and they can therefore direct more resources

to research and education.