Two powers, two models: how the US and China manage economic imbalances

Published by Veronica Campostrini. .

United States of America Asia Importexport Trade balance Foreign market analysisThe trade war between the United States and China has dominated international economic debate for years, fueled by tariffs, protectionist measures, and geopolitical tensions. However, media attention has often focused exclusively on the trade balance between the two countries—that is, the difference between exports and imports of goods. This is a useful indicator, but a limited one.

To fully grasp the complexity of the economic relationship between the two powers, it is necessary to adopt a broader perspective: that offered by the balance of payments, the accounting tool that records all economic transactions between a country and the rest of the world. Through this lens, it is possible to understand the structural dynamics that influence the economic strategies of the United States and China, both in the bilateral and global contexts.

The Balance of Payments: What It Is and Why It Matters

The balance of payments is an accounting system that summarizes all economic flows between a country and the rest of the world over a given period. It is divided into three main components:

- Current account: includes the trade balance (goods and services), income from capital and labor, and unilateral transfers (such as remittances from emigrants).

- Capital account: records non-recurring capital transfers and transactions involving intangible assets.

- Financial account: tracks capital movements in and out of the country, such as direct investments, portfolio investments, and changes in official reserves.

A fundamental but often overlooked point is that the balance of payments is always balanced. This does not mean that each individual item is in equilibrium, but rather that a deficit in one section must be offset by a surplus in another. For example, a trade deficit necessarily entails an inflow of capital or a reduction in foreign currency reserves. In the absence of these adjustments, pressure builds up in the currency market, and exchange rate movements help restore equilibrium.

The Case of the United States

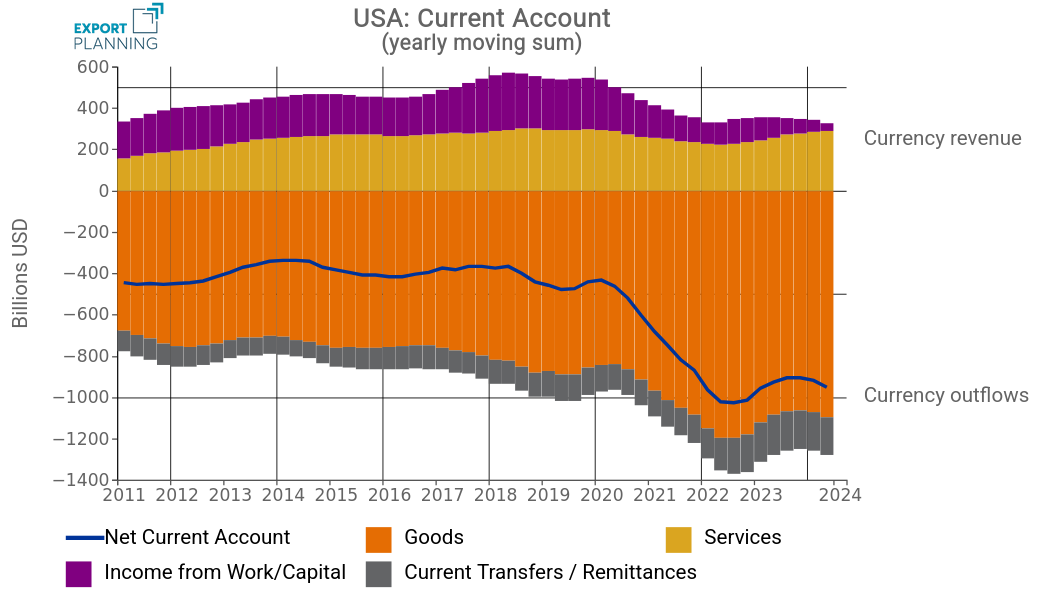

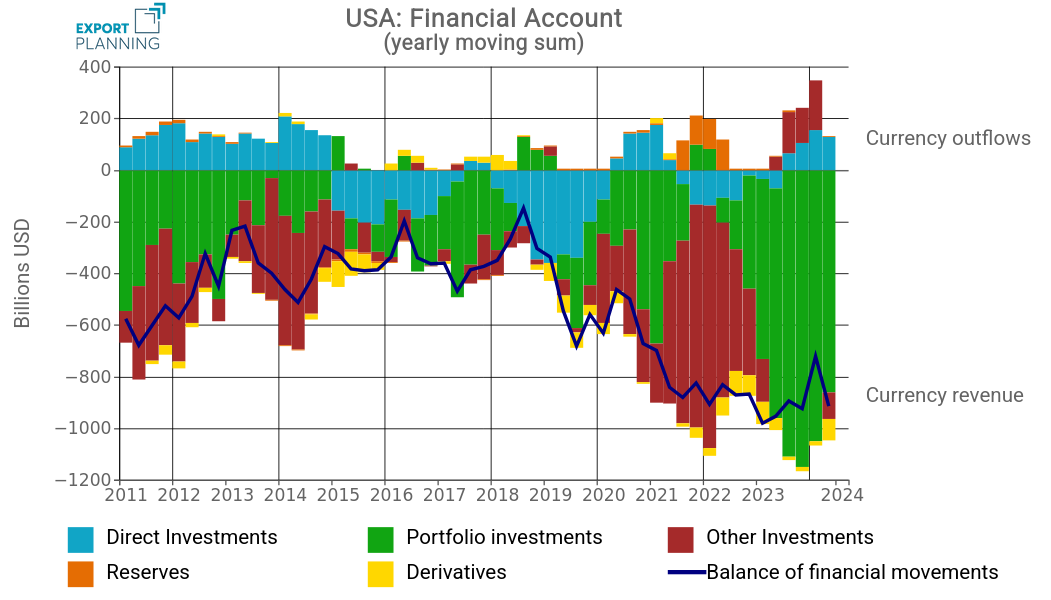

The data analysis highlights the following points:

- The substantial trade deficit in goods is partly offset by a surplus in services and income from capital, i.e., profits generated by U.S. investments abroad.

- However, in recent years, despite an improvement in the services balance and a slight reduction in the trade deficit, the overall current account has not benefited much. The reason? A sharp decline in capital income has weighed on the final outcome.

- The deficit remains manageable, thanks to a strong and consistent inflow of foreign capital, particularly in the form of portfolio investments.

USA: Current Account and Financial Account, Annual Moving Average

|

|

Source: ExportPlanning elaborations

Recent developments further confirm a now-structural dynamic that sets the American economy apart in the global landscape:

- A persistent goods deficit, mitigated by a strong services surplus, driven by high-value-added sectors such as finance, technology, consulting, and media.

- A steady inflow of capital, attracted by the stability of the U.S. economic system and the strategic importance of its financial markets. U.S. Treasury securities remain among the most sought-after investment instruments globally.

- The key role of the dollar, as a reserve currency and international medium of exchange, which allows the United States to finance its imbalances more advantageously than other countries.

In short, the United States enjoys a rare and structural advantage: it can sustain chronic trade imbalances thanks to global confidence in the dollar and the appeal of its economic and financial system. A precarious equilibrium, yet surprisingly sustainable due to strength, reputation, and centrality.

The Case of China

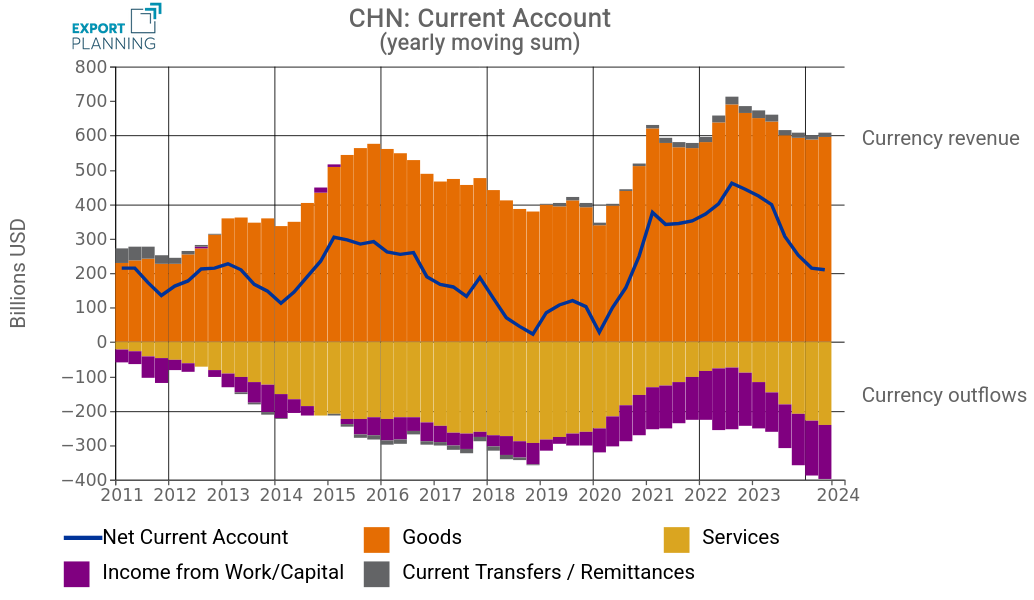

The most recent data on China’s balance of payments indicate a significant shift that emerged during the post-pandemic recovery phase. The strong improvement in the current account balance was not driven solely by the trade surplus but also—until 2023 in particular—by a reduction in the services deficit.

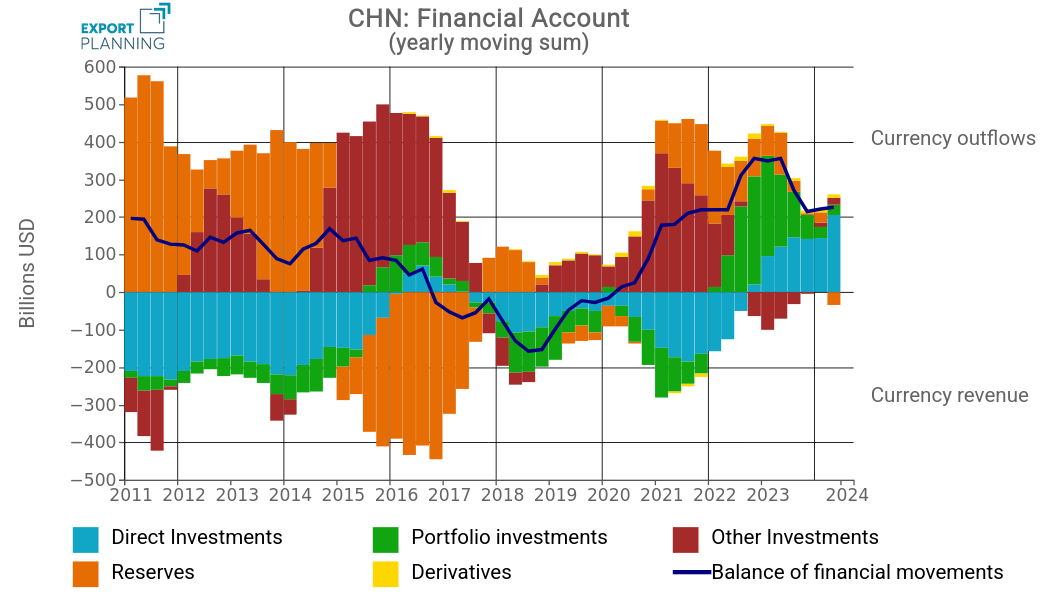

On the financial account side, a notable evolution stands out: over the past three years, the balance of foreign investments has turned from negative to positive. In other words, China has increasingly begun to use its vast foreign currency reserves—generated by exports—to acquire companies and infrastructure abroad, thereby strengthening its global economic presence.

China: Current Account and Financial Account, Annual Moving Average

|

|

Source: ExportPlanning elaborations

These developments confirm a strategy fundamentally different from that of the United States: while Washington relies on its financial markets and the strength of the dollar, Beijing focuses on a structural trade surplus and the accumulation of foreign assets. The Chinese model rests on three pillars:

- A persistent trade surplus, which ensures a stable inflow of foreign currency—especially dollars—later reinvested in U.S. Treasury securities or in strategic acquisitions abroad.

- Active exchange rate management, aimed at containing yuan appreciation and maintaining the competitiveness of export industries.

- An export-oriented economy, in which domestic demand, although growing, has not yet fully realized its potential.

In summary, China is determinedly pursuing an export-led model, supported by targeted exchange rate policies and an increasing international economic presence. A strategy aimed not only at economic growth but also at the strategic expansion of its global influence.

Conclusion: Structural Imbalances, Divergent Strategies

The balance of payments provides a much more comprehensive perspective than the simple trade balance. It reveals how the imbalances between the United States and China stem from fundamentally different economic models:

- The United States leverages its financial system and the centrality of the dollar to attract capital and sustain high levels of consumption.

- China pursues a strategy based on exports, exchange rate control, and an active foreign economic policy.

In between, trade wars risk acting on partial levers, such as tariffs, overlooking the complexity of global flows of goods, services, and capital. Only a systemic vision can guide more effective and sustainable economic policies capable of addressing real—not just apparent—imbalances.