Chinese Exports Between US Protectionism and Overcapacity

Published by Simone Zambelli. .

Asia Export Uncertainty Trade war Global economic trends

The adoption of protectionist measures by the United States, particularly through the imposition of tariffs on a wide range of foreign goods, is having and will continue to have a significant impact on international trade dynamics.

One of the most significant aspects concerns the closing of the U.S. market, especially toward China, which in the second quarter of 2025 alone saw a sharp reduction in its commercial penetration capacity, marking a nearly 30% drop in its exports in dollars to the USA.

Faced with this restriction, Chinese companies have had to relocate their surplus production shares, trying to redirect the quantities no longer absorbed by the United States toward other international markets. But in which sectors does this phenomenon seem to materialize the most?

Commercial reallocation of Chinese exports: a sectoral overview

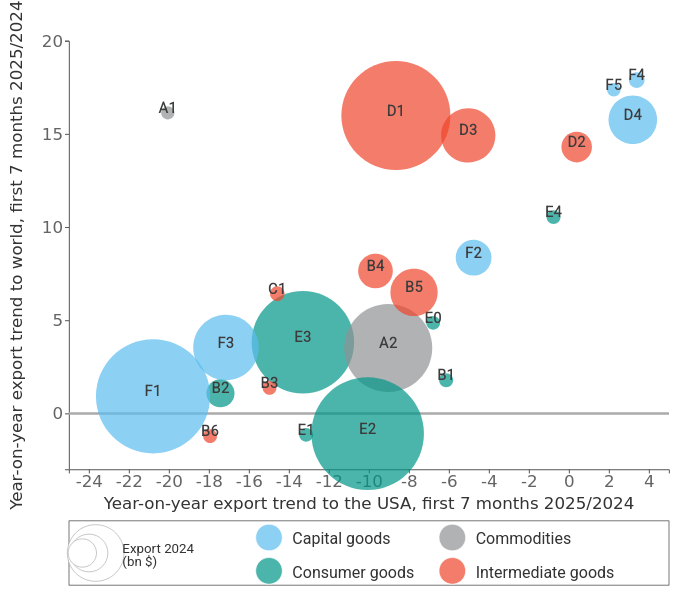

The following chart shows the year-on-year change in Chinese exports in dollars during the first seven months of 2025: on the horizontal axis is the trend toward the United States, while on the vertical axis is the trend toward the rest of the world (excluding the USA). The size of the bubbles represents the total value of exports recorded in 2024, thus highlighting the relative weight of each sector.

Chinese exports by industry

(Year-on-year changes in dollars)

Source: ExportPlanning

Data analysis highlights two major clusters into which Chinese industry can be divided.

The first cluster includes the sectors where the contraction of exports to the United States was limited and largely offset by an increase toward other markets. Here, Chinese industry shows strong resilience, managing to redirect lost sales without losing competitive momentum. These include:

- non-electronic investment goods (F2, F4, F5), distinguished more by technical efficiency and additional services than by price;

- components (D1-D4), where stable relationships with client firms are decisive;

- health products and instruments (E4), where competition is played out on quality and innovation.

The second cluster, on the other hand, includes the most penalized sectors, where tariffs have had a profound impact and the ability to compensate with other markets has been modest. Among these:

- consumer goods (particularly E2 and E3), historically a pillar of China’s industrial development;

- industrial raw materials (A2) and intermediate goods (B1-B6), sectors where competition is mainly price-based;

- finished electronic goods (F1), for decades the emblem of China’s role as the world’s factory, now increasingly contested by low-labor-cost countries;

- means of transport (F3), a sector that also reflects the difficulties currently faced by the electric vehicle industry worldwide.

Looking ahead

The extent of the commercial reallocation process between the U.S. and China has not been homogeneous. It has shown different intensities and modalities depending on the export segments, reflecting both the structural characteristics of the sectors involved and the specific adaptation strategies implemented by exporting firms. In this sense, the analysis of the effects of U.S. tariffs on Chinese exports reveals the complexity of the adjustment mechanisms generated within the global trade system, offering significant insights into the dynamics of competition and redistribution of international goods flows.

Some sectors have indeed suffered a sharp decline in sales to the U.S. market without being able to offset it elsewhere, while others have shown remarkable ability to redirect their supply toward new commercial outlets.

This results in a multifaceted picture: alongside structurally more competitive sectors resilient to tariffs, there are others more vulnerable, whose dependence on price or the U.S. market makes adaptability to the new context more complex.

China’s ability to quickly reorient some trade flows nevertheless demonstrates the flexibility of its production system, but risks amplifying already existing imbalances: overcapacity in many sectors, downward price pressures, and tensions with trading partners facing more aggressive competition.

In the coming months, it will be crucial to observe the reaction of other major exporters and destination markets: on the one hand, consumers and importing firms could benefit from more affordable goods; on the other hand, governments could feel compelled to adopt defensive tools in turn to protect domestic industries. In this scenario, Chinese exports will continue to represent a key factor not only for the global economy but also for the balance of international geopolitics.