The Dollar in the Eye of the Storm

Tariffs, Uncertainty: The Decline of a Dominant Currency?

Published by Veronica Campostrini. .

United States of America Macroeconomic analysis Dollar Europe Foreign market analysisWith the beginning of Donald Trump’s second presidential term, America has decisively embarked on a new protectionist path. While U.S. protectionism in the late 18th century aimed to support a nascent industry, today Trump uses it to attempt a reversal of course, breaking sharply with the principles and rules of multilateralism.

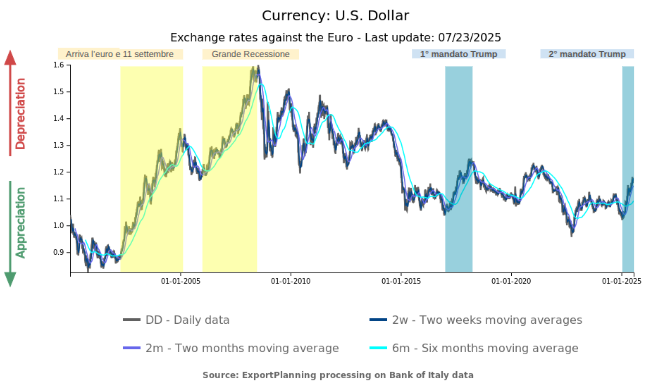

But the new face of American trade policy is not only reflected in trade flows: it has also shaken confidence in the U.S. currency. Since January 2025, with Trump’s return to the White House, the dollar has entered a persistent decline. This trend intensified in April with the introduction of a new wave of generalized tariffs that pushed the euro toward 1.18 USD. A clear signal: the dollar is losing ground—and with it, part of its international status.

Source: ExportPlanning

Uncertainty as a Tool of Governance

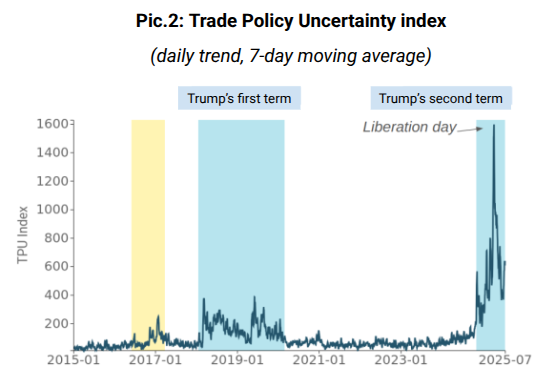

During his first term, Trump used tariffs strategically, in a way that markets could interpret. Today, U.S. trade policy resembles more a minefield than a structured strategy. Sudden proclamations, contradictory retractions, and inconsistent measures have caused a surge in the Trade Policy Uncertainty Index, which has reached new historic highs—far exceeding the peaks seen during Brexit or the tariff conflict with China.

Source: ExportPlanning

This uncertainty, once episodic, has now become systemic. And it can directly undermine the dollar’s credibility as a safe haven. During the recent Iran crisis, the reaction of the U.S. currency was modest—a sign that investors no longer automatically turn to the greenback as a shield against volatility.

The “Safe Haven” Status Wavers

Traditionally considered the ultimate safe asset—thanks to the depth of U.S. financial markets, its liquidity, and America's economic centrality—the dollar is now showing some cracks. More and more international investors view the United States not as a buffer against crisis, but as a trigger for new instability.

Despite Federal Reserve intervention and economic resilience, dollar reserves in central bank portfolios have started to decline. According to IMF data, the share of global reserves held in dollars fell from 57.79% (Q4 2024) to 57.74% in Q1 2025. In contrast, the euro rose to 20.06%. A modest, but symbolic, shift.

Economic Resilience That Masks Weakness

Paradoxically, the U.S. economy is holding up. After growing by +2.8% in 2024, GDP in the first half of 2025 has slowed but remains positive: according to the St. Louis Fed Economic News Index: Real GDP Nowcast, the second quarter could close at an annualized +1.6%. However, this growth is supported by temporary factors.

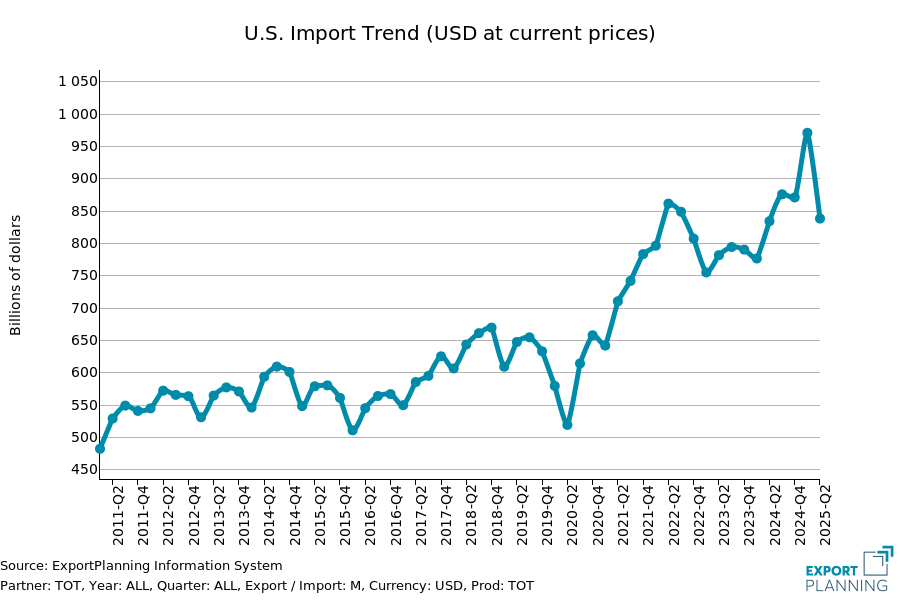

In the first quarter, companies rushed to build up inventories ahead of new tariffs. In the second, as ExportPlanning data shows, imports fell sharply—a sign that tariff instability is holding back trade flows. Meanwhile, inflation has resumed its upward trend, rising from +2.3% in April to +2.7% in June. Inflation expectations are increasing, prompting consumers and businesses to front-load purchases—a behavior that could quickly fade.

Source: ExportPlanning

Asymmetric Protectionism and the Risk of Global Deflation

American protectionism does not stop at U.S. borders. The tariff barriers imposed by Washington have ripple effects: in exporting countries, limited access to the U.S. market creates excess supply that spills into other markets, fueling deflationary dynamics globally. For the Eurozone, the timing could not be worse. The combination of tariffs and a weakening dollar is hurting European exports, eroding margins and competitiveness.

According to ExportPlanning estimates, EU exports to the United States remained in positive territory in Q2 2025. This result is artificially supported by stockpiling—especially in sectors such as pharma, still exempt from tariffs, but where action is expected. Looking ahead, absent a concrete agreement in ongoing Brussels-Washington negotiations, U.S. demand for European goods is expected to face a significant decline.

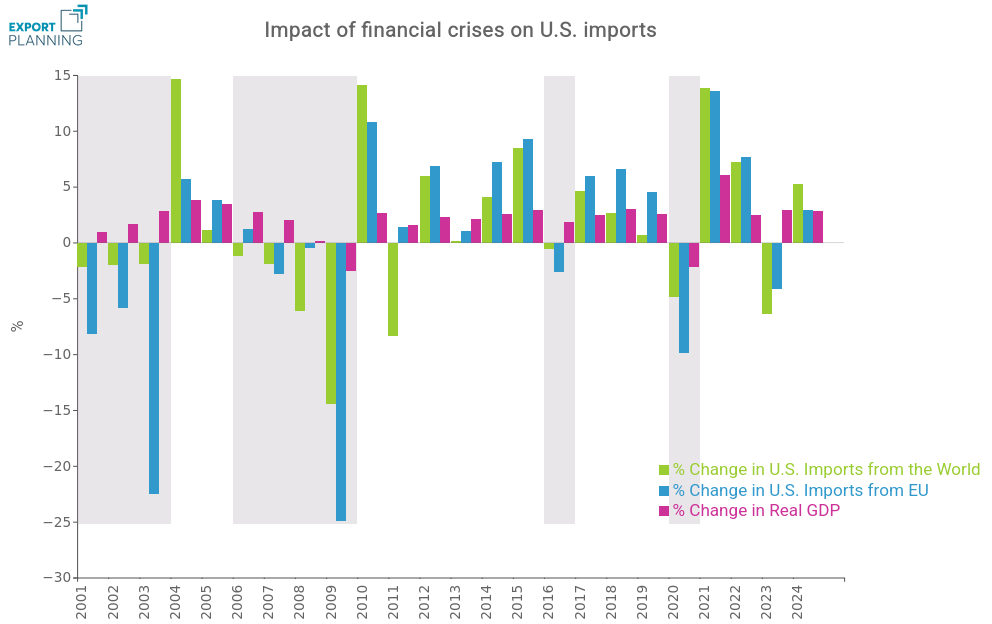

As recent history suggests, phases of pronounced dollar weakening have occurred during major financial crises that spilled over into the real U.S. economy. Three episodes are particularly illustrative.

The first was the bursting of the Dot-com bubble in the early 2000s, which triggered the century’s first dollar depreciation phase—resulting in a 22% real decline in U.S. imports from Europe.

The second was the subprime mortgage crisis, which emerged in 2006–2007. During that time, U.S. imports from the EU had already contracted by 5% in the years leading up to the peak of the 2009 Great Recession.

The third, more recent, was not tied to a financial crisis but to the second half of 2016, during the campaign that led to Donald Trump’s first election. Even then, the dollar experienced a strong depreciation against the euro—likely linked to political uncertainty and a shift in trade policy—which led to a decline in overall and EU-specific U.S. imports.

Source: ExportPlanning

Looking to the present, what sets this phase apart is the intensity and persistence of the current dollar depreciation. If this trend continues, combined with a hostile trade policy, the impact on European exports could be significant. Unlike Trump’s first term, today’s uncertainty is more systemic—at levels far higher than during his first administration.

For Europe, this implies not only an economic challenge but also the need to redefine its trade strategy in a global context that is less open and increasingly unstable.

Diverging Monetary Policies, Diverging Confidence

Monetary policies also reflect the transatlantic tension. While the ECB continues its rate-cutting cycle, the Federal Reserve remains cautious, caught between political pressure to lower rates and the need to contain inflation. Trump is pushing for an expansionary monetary policy, but uncertainty threatens to nullify its effects.

The interest rate differential, which should support the dollar, is instead offset by declining confidence in U.S. assets. Downward pressure on the dollar is no longer merely cyclical—it has become structural.

Conclusion: Centrality Under Scrutiny

The dollar remains at the heart of the global financial system. It is still the most traded and widely used currency for international invoicing. But growing signs—declining reserves, currency market volatility, reduced appeal as a safe-haven asset—suggest that its centrality is now less solid.

There are still no credible alternatives to the dollar, but its status is no longer unchallenged. Its future will depend on the coherence—or incoherence—of American policy, the evolution of geopolitical relations, and the confidence markets place, or not, in Washington’s ability to lead rather than destabilize the global economy.