The political Debate in Peru worries Financial Markets

The sanitary and economic crisis is now compounded by the prospect of a new unrepresentative President

Published by Luigi Bidoia. .

Exchange rate Covid-19 Exchange ratesThe pandemic is creating a strong differentiation between different areas of the world. Latin America is, without any doubt, the most penalized one, both because of pre-existing economic difficulties and because of its weaker capacity to manage the health emergency. In the IMF's most recent forecast scenario, the region is projected to grow by only 4.6% in 2021, against a 7% drop in economic activity levels in 2020. Only in 2022 will Latin America's activity levels be higher, and only slightly, than pre-pandemic levels.

The sanitary emergency has brought to light the weakness of the continent's health structures, but also of its political institutions, which are incapable of proposing and implementing effective strategies to contain the contagion.

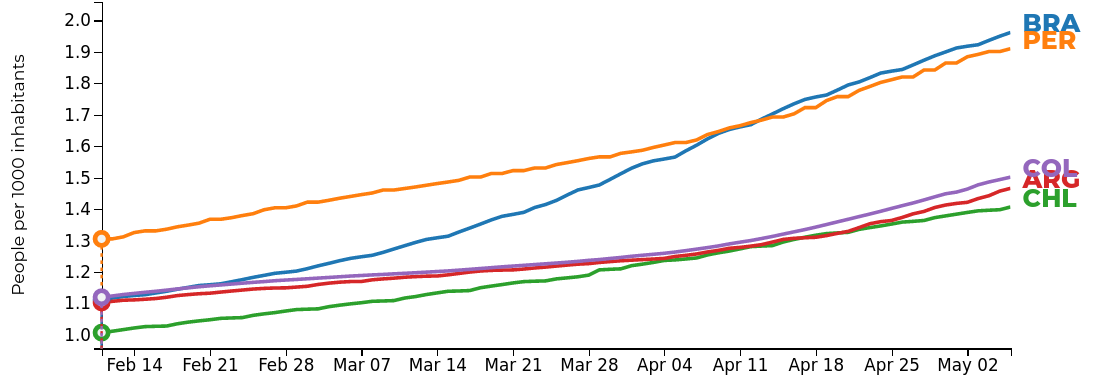

Brazil, led by the "denier" Bolsonaro, is certainly the most dramatic case. But, equally dramatic, is the sanitary crisis in Peru, where the attempt to implement lockdown policies has failed due to the high share of irregular labor, that has not made possible for workers and their families to comply with government restrictions. As a result, Peru has joined Brazil in the number of deaths from Covid19 as a percentage of the population.

COVID-19 deaths per 1000 population

A political crisis is now adding to the sanitary and economic crisis. Pedro Castillo (a professor, close to the peasants and the poorest classes of the country) and Keiko Fujimori (daughter of former president Fujimori, on whom there are accusations and convictions for corruption, murders and serious violations of human rights) unexpectedly won the first round of the presidential elections on April 11. In the runoff election on June 6, two opposing economic and social visions will be compared: the first is statist, an expression of forgotten Peru and the poorest regions; the second is neoliberal, an expression of the capital and the wealthiest classes in the country. The confrontation between these two extreme positions is radicalizing the political clash, foreshadowing a future political and institutional weakness of the country, whoever emerges as the winner.

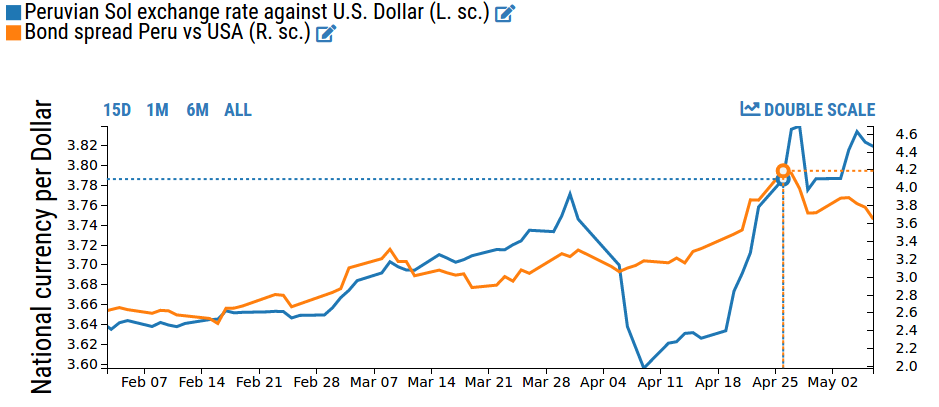

The overlapping of these crises was registered by the financial markets with a parallel weakening of the Peruvian currency and an increase in interest rates. The chart below shows the exchange rate of the New Sol per dollar and the spread between the rates on Peru's 10-year bonds compared to those in the United States

As can be seen in the graph, from mid-February to today, the exchange rate has gone from 3.65 to 3.82 sols per dollar; the rate spread from 2.6 to 3.8. It is interesting to note that in the days leading up to the April 11th elections, the prospect of victory by less radicalized candidates had in part reduced the rate spread and, above all, led to a significant appreciation of the Nuevo Sol. The phase of weakening of the exchange rate and the increase in rates then resumed quickly after April 18th, when the result of the elections was made official.

Also in the case of Peru, the sanitary crisis is increasingly revealing how the quality of a country's institutions and political confrontation is fundamental to its social and economic development.